Any semi-experienced developer would have used Git branches as part of their development workflow. They are very important for effective collaboration and isolating under-development code from production code. Developers often use branches to try out new ideas, tools, etc and then delete the branch once done. You would agree with me when I say that working with branches in Git is a breeze, so much that most of us take this feature for granted and never stop to think about the underlying implementation or appreciate its lightweightness.

Most of us, who have never worked with any other version control system, will not be able to appreciate the ease of working with branches in Git. Older version control systems like Subversion usually took seconds or minutes (depending on the size of repository) to create a new branch. On the other hand, creating a new branch in Git is almost instantaneous.

In this post, I am going to explore the inner implementation of branching in Git and help you figure out: How are branches in Git so lightweight?

Branches as pointers

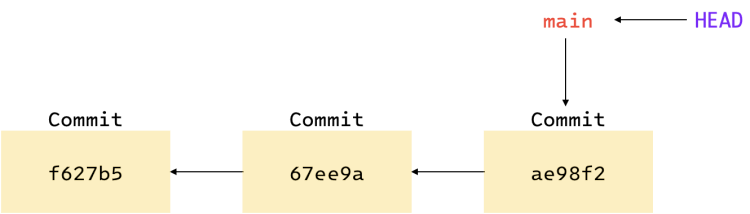

In the previous post, we learnt that commits in Git are simple objects with a reference to the snapshot of the code at the time of commit and a reference to the parent (previous commit).

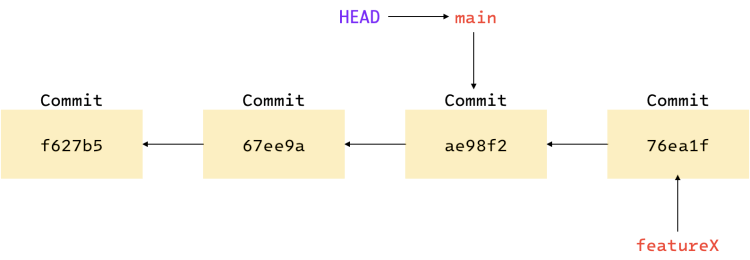

Similarly, branches in Git are simple movable pointers which point to one of the commits. When you make a commit, the current branch’s pointer automatically moves to the new commit.

main branch. It is just another branch which

is created by default by Git for you to start working on.

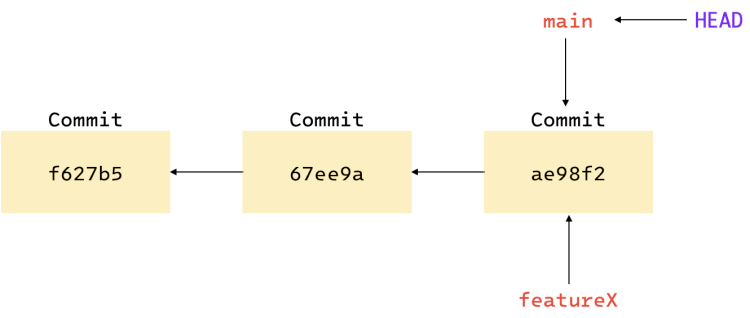

Creating a new branch

When you create a new branch, a new pointer is created that points to the last commit made in the

current branch. The following command creates a new branch called featureX:

git branch featureX

About HEAD

In order to know which branch you are currently on, Git maintains a special pointer called HEAD.

It points to the current branch. In the figures above, you can see that HEAD is pointing to the

main branch.

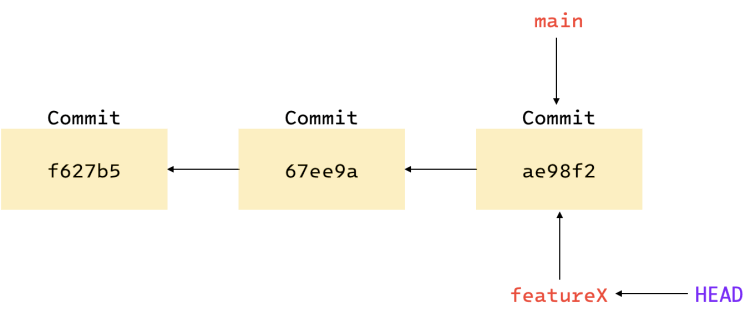

The command git branch <branchName> only creates a new branch, but does not switch to it. In order

to switch to the new branch, in this case featureX, you need to run:

git checkout featureX

As you can see in the figure below, switching to featureX moved the HEAD pointer.

You can create and switch to a new branch in a single command:

git checkout -b featureX

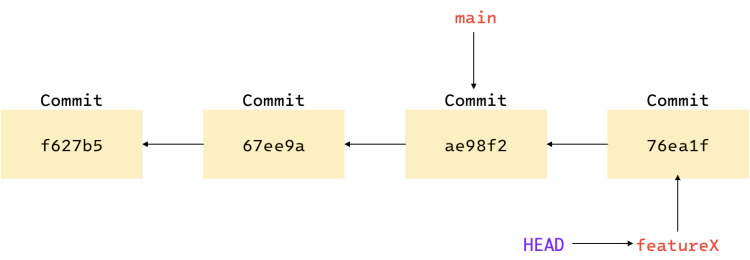

What happens when you make a commit now?

A new commit object is created and the featureX branch pointer moves to the new commit, along with

the HEAD pointer.

Moving back to main

If you move back to main branch now, the HEAD pointer will again point to the main branch, as

shown below. Also, your files will be reverted back to the snapshot that main points to.

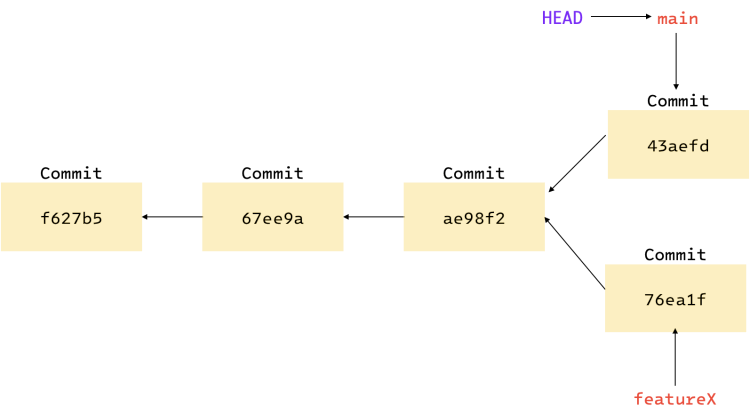

If you make a new commit now, your project history will diverge. A new commit will be created which

will be isolated from the commit you made in the featureX branch. The figure below should help you

get a better understanding.

Commits in both the branches are isolated from each other. Switching to a branch will revert your files to the snapshot that the branch points to.

As already mentioned in the post about customising git logs, you can view the divergent history of your repository using the --graph flag.

From Git version 2.23, Git has introduced the switch subcommand which can be used to switch

between branches.

- To switch to a branch, run:

git switch <branchName>. - To create and switch to a new branch:

git switch --create <branchName>. - To return to the previously checked out branch:

git switch -.

Conclusion

A branch in Git is a simple file which contains the 40 character SHA-1 checksum of the commit it points to, making them extremely cheap and easy to create and destroy. Since we are recording the parent of commit, as mentioned in the previous post, Git can easily find the common merge base of two branches, making branches easy to use and merge.

Wondering how the git branch file is 41 bytes in size?

40 bytes for the 40 character checksum and 1 byte for the newline.