After a series of posts that focused on the practical usage of some of the Git concepts, this post, once again, focuses on the internals of Git. I will tell you about the way Git works behind the scenes when we make a commit. This knowledge will help you understand why branching in Git is fast and extremely lightweight as compared to other version control systems, when we cover branching in a later post.

How does Git store the commit internally?

If you have read my post covering the internals of Git storage,

you’d know that Git stores the full snapshots of your files when they change and are committed. When

you make a commit, a commit object is created by Git which contains a pointer to the previous

commit(s) (null in case of first commit), a pointer to the snapshot of the content that has been

committed, and metadata like author’s name, email and the commit message.

How is the snapshot created?

Assume that your repository’s directory structure looks like:

dir-1/

|-- 1-bar.txt

|-- 1-foo.txt

`-- dir-2/

`-- 2-foo.txt

1 directory, 3 files

Assuming that all the files are modified and staged, Git first computes the checksum (SHA1 hash) of each file and stores those checksums as blobs.

| file | blob checksum |

|---|---|

dir-1/1-bar.txt |

da39a3 |

dir-1/1-foo.txt |

1eaf2e |

dir-1/dir-2/2-foo.txt |

5f2a25 |

shasum <filename> to calculate the SHA1 checksum of a file.

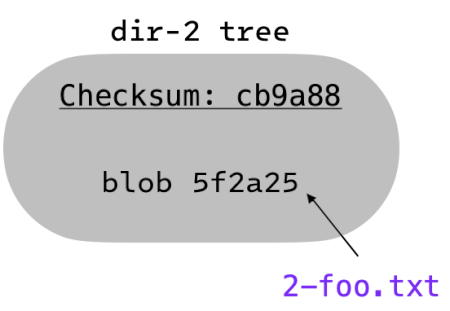

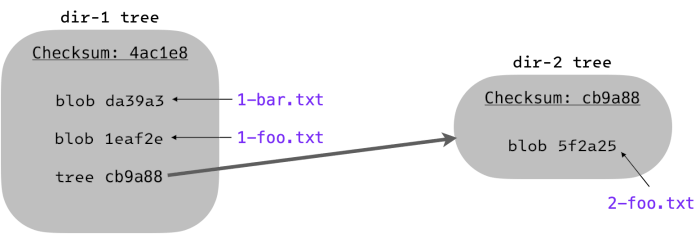

Next, Git calculates the checksum of each subdirectory (essentially checksum of all blobs in the subdirectory) and stores them as trees.

So, the “tree” for dir-1/dir-2 contains the blob checksum of dir-1/dir-2/2-foo.txt.

The “tree” for dir-1 contains the blob checksums of 1-bar.txt and 1-foo.txt, in addition to

the tree checksum of dir-2.

This is the final snapshot

To get the SHA1 checksum of a directory, you can run

shasum <file1> <file2> .. <fileN> | shasum

where file is a file inside the directory and its subdirectories.

Storage of commit

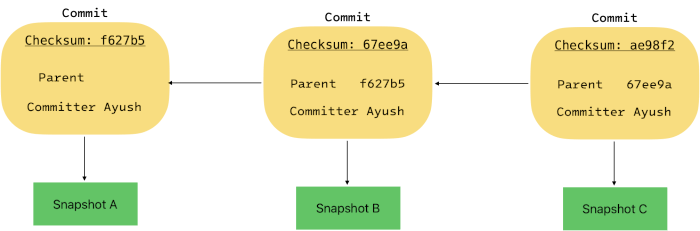

As already mentioned above, the commit object contains a pointer to the snapshot. In this case our

tree checksum for dir-1 would be the snapshot and its pointer is saved in the commit object.

If it is the first commit of the repository, the pointer to the previous commit is null. The next

commit will point to the first commit, the third commit will point to the second commit and so on.

In Git language, the previous commit is called a commit’s parent.

Conclusion

In this post, you got a glimpse of how Git commits work internally and probably have an inkling of the reason behind Git’s lightweightness and speed.