If you have worked with Git, you must have come across merge commits. These commits are not created every time you merge, but only on some special scenarios. In this post, we will learn about merge commits and when are they created. At the end of the post, I will also provide a way to avoid them.

First, the simple fast-forward merge

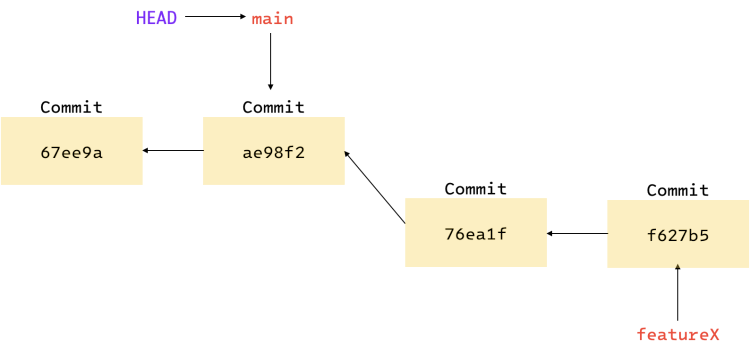

Consider that you have a branch named featureX which diverges from the main branch as shown

below.

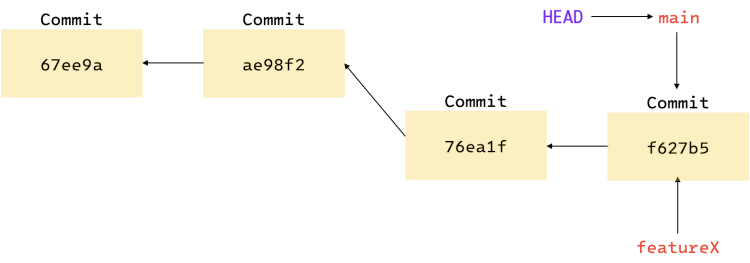

If you try to merge featureX into main using git merge featureX, you will see the text

Fast-forward in the merge output. Git uses this merge strategy when the commit pointed to by the branch that is being

merged into - main in this case - is a direct ancestor of the branch that is being merged -

featureX in this case.

In other words, if you start following the parent starting from the commit

pointed to by featureX and you reach the commit pointed to by main after some jumps, Git will

simply move (fast-forward) the main branch pointer to the commit pointed to by featureX.

main branch as an example. I don’t mean to convey that merges can only happen into

the main branch. Any Git branch can be merged into any Git branch.

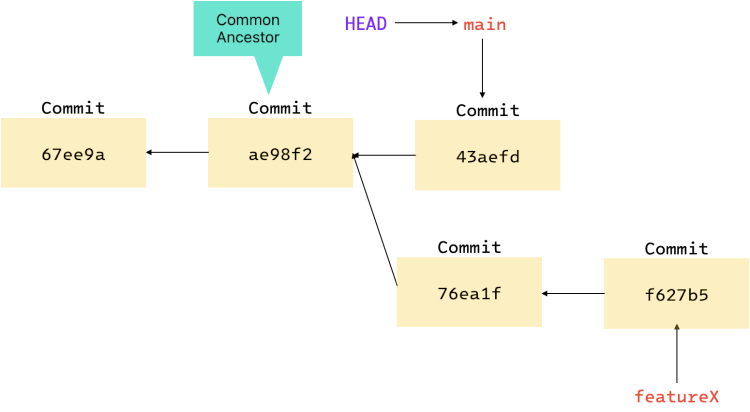

When the main branch is NOT an ancestor of your feature branch

Consider the scenario below where the main branch has moved ahead from the point where featureX diverged.

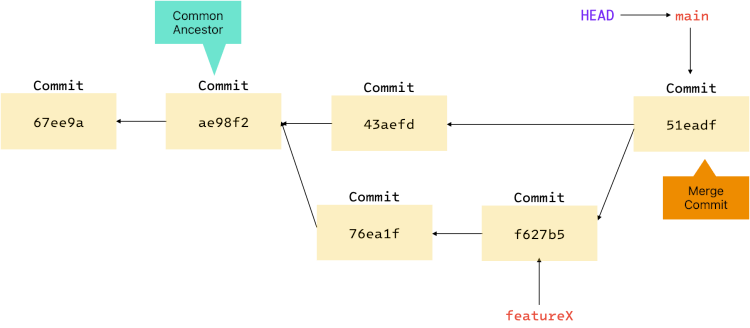

In this case, the commit pointed to by main is not an ancestor of the featureX branch. So, Git

tries to find the common ancestor of the main and featureX. Then, Git performs a three-way merge

between the common ancestor commit, the commit pointed to by main, and the commit pointed to by

featureX. It creates a new snapshot that results from this merge and creates a “merge commit” on

the main branch (or the branch being merged into).

Avoiding merge commits

To avoid “merge commits”, you can rebase the featureX branch on the main branch. After the rebase, the commit pointed to by main will become an ancestor of featureX. To learn more about rebasing, I suggest you read my post introducing git-rebase.